To die in one's sleep. . . so basic to the cauldron of human fears,

subject matter to ancient rhymes and holy sonnets, the arts and literature,

laden with layers of mythology, coloring folklore with creatures of

the night, concoctions of superstitions, and nostrums of nightmare

preventions. Cloaked in mystery and dread, it has acquired a motley

of names and acronyms – Sudden Unexplained Death Syndrome. SUDS,

Sudden Unexpected Death in Sleep, Sudden Unexplained Nocturnal Death

Syndrome, SUNDS, nightmare deaths, sudden night deaths

– as science pokes through the muddle of myth and folklore,

searching for etiologies and pathogenesis that can shed light into

this mysterious fatal affliction that visits presumably healthy young

men in their sleep, more commonly in the Southeast Asian and Pacific

Rim countries and Polynesian populations believed to have migrated

from South East Asia centuries ago.

First reported in the Philippines in 1917, 'sudden

night deaths' or SUDS (sudden Unexpected Death in Sleep) has been

attributed to bangungot (bangungut

- from the Tagalog root words of "bangon" (to rise) and

"ungol" (to moan). It is a syndrome wrapped in folklore

and myth, that consists of a nightmare, commonly occurring in nocturnal

sleep, frequently after a heavy meal that is often accompanied by

alcohol, most often in young males, aged 25-44, presumably healthy,

without any known cardiac illness.

Risk

profile

Young males

Age: 25-44

A heavy meal

Alcohol use

Presumably healthy with

no prior heart problems

Fainting

Family history

of unexpected death |

. |

In

the Philippines, bangungut (SUDS) has been so linked to gluttonous

eating and bacchanalian drinking, to the exclusion of other symptoms

or warning signs. Fainting and family history do not raise red

flags. But South East Asian studies suggest that a history of

fainting with a positive family history increases the chance

of dying of SUDS in the next five years.

A review of SUDS cases (Munger and Booton) from Death Certificates

filed in Manila during 1948-1982 showed the same characteristics:

96% male, mean age 33 years, modal time of death 3:00 a.m. The

deaths were seasonal, peaking in December-January, and the SUDS

victims were more likely than diseased controls to have been born

outside of the Manila area.

A 2003 UP health survey on SUDS among young Filipinos reported

43 deaths per 100,000 annually. |

How often bangungut becomes fatal is unknown. Many cases are never

reported, especially in the rural areas where dying in your sleep

is an accepted event in the folklore of death. Many know others who

died in their sleep. Many more are 'survivors' of one or more attacks,

with descriptive details of bangungot -type nightmares– of sleep

paralysis, of falling from a mountain or into a deep abyss, of the

creature in the dark standing by the bedside. How many of these are

actually near-death or near-bangungut experiences or are they merely

generic ingredients to culture-flavored nightmares?

|

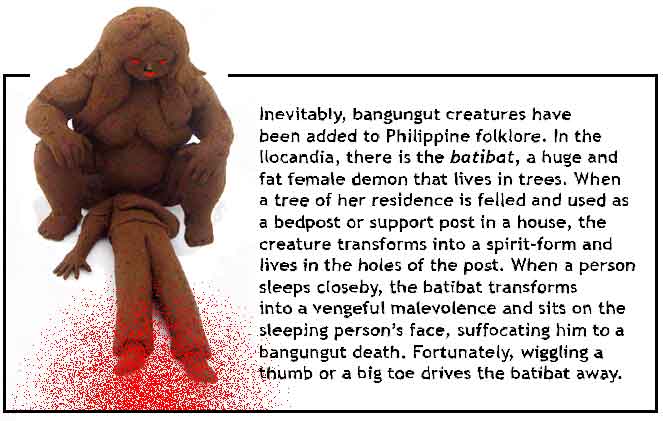

| Note: I have to begrudge the Ilocandia

myth makers. Why the need to invent "Batibat?"

To die in a bangungut nightmare is uugghh-dreadful enough.

But to die with the the fat and vengeful "batibat"

seating on your face. Oh, mercy me. |

"Batibat" clay sculpture

by Alvin Barcelona, Brgy. Lumingon, Tiaong, Quezon (4"x5") |

|

Although there are witness reports of "moaning, groaning, gasping,

choking, frothing, and labored breathing," as often, patients

are found dead, in seeming peaceful slumber, without the sounds of

terror or any evidence of a terminal struggle.

In a "macho-culture" with a penchant

for drinking, often to oblivion, and accompanying this libatory indulgence

with a smorgasbord of "pulutan," pancreatitis became the

popular and preferred "point-to diagnosis." (see pancreatitis,

below).

In a country with more than 7000 islands and more

than 70 indigenous communities, where albularyos and medicos minister

to the end-days, diagnosing fainting spells by tawas

and treating them with a bulong and/or orasyon,

where the night worlds are ruled by the frightful creatures of myths

and superstitions – the tikbalangs, kapres, asuwangs, white

ladies and pontianaks, where death's ways are accepted with funereal

fatalism as God's will, karma, or bangungut. — alas, the true

incidence of bangungut / SUDS is probably a-long-time-coming before

it gets revealed to the scrutiny of science.

|

NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCIES, FOOD MYTHS, ALCOHOL,

STRESS AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

The occurrence of SUDS in Asian populations, the

decline among SEA refugees after immigration to the US, the elevated

risk among migrants in Manila and seasonality of occurrence (Munger

and Booton) implicates stress, environmental factors and nutritional

deficiencies.

| Alcohol has long been part of the bangungot story. However, it's role is not in causing hemorrhagic pancreatitis, but rather, in inducing potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias. (See Brugada syndrome below) |

|

Of the Thai workers in Singapore, nutritional deficiencies

were implicated, particularly thiamine and potassium. However, there

is no information as to whether potassium levels were obtained, or

how severe the hypokalemia was.

Stress has been considered in

the etiology of SUDS, reported in usually high numbers in healthy

young Southeast Asian men, especially in various refugee populations

and migrants communities. With increasing length of residence in the US,

SUDS rates markedly declined. But if stress alone is causative, how

to explain its relative absence in the many other countries ravaged by

war and poverty, and driven to dispersions and economic diasporas.

In the Philippines, alcohol has always been part of the bangungot narrative. However, most cases of bangungot do not involve alcohol use; and when it does occur in the setting of heavy alcohol use or binging, or the combination of excessive alcohol and over-eating, it is often attributed to alcohol-induced hemorrhagic pancreatitis. (See below)

Besides gorging and drinking before bedtime, certain foods myths abound.

Some warn against big noodle meals before bedtime. Too, rice cakes

at bedtime. In one rural village, seasoned imbibers are afraid to combine

beer and balut, from an anecdotal account of a father and two sons

who succumbed to bangungut deaths - the deadly combination, prologue

to their dreadful end. |

THE

SCIENCE

THE OLD AND THE NEW

Inevitably, science went forging

and fishing into the sea of folklore and myths. In the recent decades,

battling through ghouls and night hags, armed with the old and new

tools of technology and the disciplines of research, digging into

new world of genetic mutations, it has emerged partially victorious,

providing us alternatives to the old and overused pancreatitis-diagnosis,

with new theories and etiologies — the Why-What-and-How of

unexpected sudden nocturnal deaths, and further adding to its lengthening

lists of acronyms and syndromes (SADS: Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndrome

from Brugada, the Long QT, or Short QT syndromes).

THE OLD . . .

ACUTE

HEMORRHAGIC

PANCREATITIS

In the Philippines, the cause of

SUDS / bangungut has been linked to acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis

attributed to a hearty or gluttonous meal often downed by a hefty

amount of alcohol. A high salt diet, contributed to by native condiments

- patis and bagoong - has been implicated. Stories

are told of bangungut attacks with the combined indulgence of beer

and balut.

| As the sole cause of

bangungut, pancreatitis is a hard-sell. Usually, acute pancreatis associated with excessive alcohol use, is rarely, if ever "silent,"

but rather quite dramatic and severe in its presentation, more

likely to present itself with more than an "ungol" (groan). |

|

| |

|

| Studies have implicated alcohol in a non-pancreatic etiologic role. A case report suggests an association between alcohol consumption and ventricular fibrillation in a patient diagnosed to with Brugada syndrome. (See below) |

|

PANCREATITIS is the inflammation of the pancreas,

the gland that sits behind the stomach, concerned with digestive enzyme

functions and production of insulin. It is connected by a ductal system

to the liver and the gallbladder, an anatomic detail of concern in

gallstone disease. Pancreatitis can be either acute or chronic. In

acute pancreatitis, there may be a history of excessive alcohol intake

or a heavy meal preceding the attack or a history of biliary colic

(gallstones) in the past. The rest are due to infections, vasculitis,

drugs, trauma, hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia. Although occasionally

mild, often the symptomatology is rather dramatic in acute pancreatitis,

with nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, distention, sweating,

rapid pulse,and shock.

Clinically, it is a hard-sell of a diagnosis

if it is to be solely implicated for cause of bangungut deaths.

As mentioned, attacks of acute pancreatitis have a rather dramatic constellation

of symptoms, running the course of hours to days, with a severity

that forces the patient to seek help or medical attention. Of course,

the pancreatitis could have been "silent" if the alcohol

was used in 'overdose' amounts, enough to cause respiratory depression,

seizures, shock, coma, and death.

Still, it will not explain the many

cases of "bangungut" deaths in the seemingly "peaceful"

scenarios of dying. Also, there are many similar "night deaths"

where autopsies failed to show any pathologic cause. And for these,

the usual fall-back is the waste-basket diagnosis of "cardio-respiratory

arrest."

However, although pancreatitis per se is the unlikely pathogenic etiology, alcohol is included in the list of substances that may unmask or modulate the pathologic and potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias that may cause sudden cardiac death. (See below)

. . . AND THE NEW

The

Brugada & QT Syndromes:

The long and short of it

The

human body has a system of quasi independent electrical circuits that

can be recorded through medically dedicated tools: the EMG-NCS (electromyography

for muscle and nerve conduction studies), the EEG (electroencephalography

for the study of brain waves) and the EKG or ECG (electrocardiography

for a print out of the heart's electrical rhythm). Fascinating, all

– electrical systems working in unison, with an endogenous power

source that usually lasts a "lifetime of average use and abuse."

Of these, it is the EKG that can provide information critical to the

immediate assessment and management of life-and-death

situations: heart

attacks and potentially fatal cardiac irregularities. To boot, it

can provide clues of rhythm disturbances and

PQRST-wave configuration abnormalities that can alert the astute clinicians

into raising red-flags, recognizing and preventing potential problems.

The ECG has been the gateway tool in the diagnoses of clinical entities

constituting a group called SADS (sudden

arrhythmia death syndrome) recognizable by its potentially fatal electrocardiographic

presentations (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, idiopathic ventricular

fibrillation,

or arrhythmias caused by electrolyte imbalances). Recent studies and

discoveries have focused on emerging entities — the Brugada

syndrome, the long-QT and the short-QT syndromes — with its

hereditary genetic defects affecting the cardiac ion channels, stripping

some layers from the myths of sudden unexpected nocturnal deaths,

providing science, etiologies and treatment options. The

human body has a system of quasi independent electrical circuits that

can be recorded through medically dedicated tools: the EMG-NCS (electromyography

for muscle and nerve conduction studies), the EEG (electroencephalography

for the study of brain waves) and the EKG or ECG (electrocardiography

for a print out of the heart's electrical rhythm). Fascinating, all

– electrical systems working in unison, with an endogenous power

source that usually lasts a "lifetime of average use and abuse."

Of these, it is the EKG that can provide information critical to the

immediate assessment and management of life-and-death

situations: heart

attacks and potentially fatal cardiac irregularities. To boot, it

can provide clues of rhythm disturbances and

PQRST-wave configuration abnormalities that can alert the astute clinicians

into raising red-flags, recognizing and preventing potential problems.

The ECG has been the gateway tool in the diagnoses of clinical entities

constituting a group called SADS (sudden

arrhythmia death syndrome) recognizable by its potentially fatal electrocardiographic

presentations (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, idiopathic ventricular

fibrillation,

or arrhythmias caused by electrolyte imbalances). Recent studies and

discoveries have focused on emerging entities — the Brugada

syndrome, the long-QT and the short-QT syndromes — with its

hereditary genetic defects affecting the cardiac ion channels, stripping

some layers from the myths of sudden unexpected nocturnal deaths,

providing science, etiologies and treatment options.

|

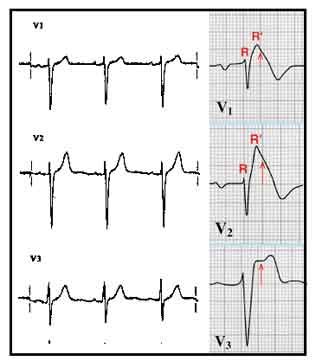

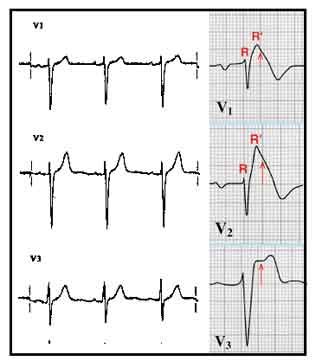

| The V1–

V3 tracings compare the normal on the left with the Brugada pattern

on the right: a terminal R' wave in lead V1, a convex curve or "coved-type"

ST elevation in V1 and V2 and a saddle-shaped ST-segment elevation

in V3. |

BRUGADA SYNDROME

In

1998, a hereditary (autosomal dominant) gene defect was found, involved

in the coding of protein components in the sodium channels in heart

cells. The channel defect causes abnormal electrical conduction in

the heart with resultant ventricular arrhythmias, including full-blown

ventricular fibrillation leading to death. Of the patients studied,

many presented with unexplained fainting spells.

ECG PATTERNS

The Brugada syndrome presents with 3 different ECG patterns. The classic

type 1 Brugada pattern consists of a right bundle branch block with

a right precordial injury pattern (ST-segment elevations that descend

and have an upward T-wave inversion ("coved type") in leads

V1 through V3). Types 2 and 3 have "saddle-back" ST-T waves,

with descending ST segments and an upright T wave; in type 2, the

T wave is upright or biphasic. A slight prolongation of the QT interval

may be noted in the right precordial leads due to the prolongation

of the action potential in the right ventricular epicardium. The Brugada

patterns differentiate from typical RBBB patterns by the absence of

widened S waves.

The classic (type 1) Brugada syndrome

presents with the coved-type ST elevation in more than 1 right precordial

lead ,V1 through V3, with or without a sodium channel blocker, with

one of the following criteria: syncope, documented ventricular fibrillation,

electrophysiologic inducibility of ventricular tachycardia, positive

family history of cardiac death younger than age 45, nocturnal agonal

respiration, self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia,

and type 1 ST elevation in family members.

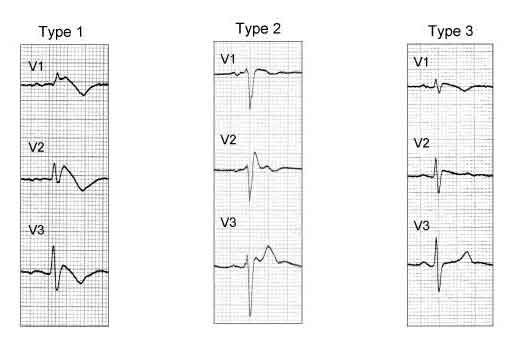

|

| ECG patterns in Brugada syndrome. According to recent consensus document, type 1 ST segment elevation either spontaneously present or induced with Ajmaline/Flecainide test is considered diagnostic. Type 1 and 2 may lead to suspicion but drug challenge is required for diagnosis. The ECGs in the right and left panels are from the same patient before (right panel, type 1) and after (left panel, type 1) endovenous administration of 1 mg/kg of Ajmaline during 10 minutes. |

| The ECG manifestations of Brugada syndrome are often dynamic or concealed and may be unmasked or modulated by sodium channel blockers, a febrile state, vagotonic agents, alpha-adrenergic agonists, beta-adrenergic blockers, tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants, a combination of glucose and insulin, hypo- and hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, and alcohol and cocaine toxicity. Brugada syndrome: second consensus conference |

| A case report decribed a patient with Brugada syndrome with VF (ventricular fibrillation) episodes consistently related to alcohol consumption. (EP Case Report: Watanabe et al. |

Types 2 or type

3 Brugada syndrome presents with ST elevations: ≥1mm in type

2 and <1 mm in type 1 in more than one precordial lead, with conversion

to type 1 Brugada ECG patters after the administration of a sodium

channel blocker plus one of the type 1 criteria.

Fortunately,

these ECG patters are rare. In Japan, it is found in less than 1%

of the population; and in the U.S.,in less than 0.5%. Of these, most

will not have any problems. But the EKG pattern, coupled with a history

of unexplained fainting, a history of a relative dying young, raises

a red-flag risk of sudden death.

In the Philippines,

a cross-sectional study done in 2003 to measure the prevalence of

Brugada type EKG pattern reported finding the Brugada type 1 (coved)

ECG pattern in 0.2% of the population and in 0.3% among males. The

prevalence of any type Brugada ECG pattern was 2%. The risk of sudden

death among individuals with this marker remains to be determined.

(http://www.jclinepi.com/article/S0895-4356(07)00434-9/abstract)

The

syndrome has been linked to SUDS, causing sudden death in apparently

healthy young people over the age 30. A study of patients with

SUNDS and their families, screened for genetic mutations in SCN5A,

the gene known to cause the Brugada syndrome, suggested that SUNDS

and the Brugada syndrome are phenotypically, genetically, and functionally

the same disorder. <http://hmg.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/11/3/337>

In Thailand, where the estimated prevalence

of SUDS is 26-38 per 100,000 population, a study on patients with

the Brugada syndrome showed a low heart rate variability at night

that may predispose to the occurrence of ventricular fibrillation

episodes.

A study done to evaluate the significance

of cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) in the Brugada Syndrome concluded

that CAN is an important risk factor in BS, and that men are susceptible

to the development of cardiac events.

The prognosis for high risk patients - abnormal

EKG with history of syncopal attacks or near-sudden death resuscitation

- is very poor, with a third at risk of a polymorphic ventricular

tachycardia within two years.

Brugada in Children / Alterations in Pubertal Hormonal Landscape

• Although rare in children and generally excluded from the Brugada debate, there was a report of 30 children and adolescents (≤16 years of age) diagnosed with the syndrome. 37% had Brugada-type EKG (1 cardiac arrest, 10 syncope) and the majority (60%) were asymptomatic. The children differed from adults in gender distribution - there was no obvious male predominance. Although it is genetic disorder of autosomal-dominant inheritance, with males and females expected to inherit the gene equally, in adults, aged 34 to 53, it manifests invariably male, ≥90%. The hormonal landscape attempts to explain the differences: the male testosterone might reduce inward calcium currents and facilitate onset of arrhythmia by shortening of action potential while female estradiol could be "antiarrhythmic" by modulating calcium current density. The hormonal changes in puberty and their electrophysiological effects may partly explain the increase of male occurrence after puberty.

TREATMENT

• ICD (Implantable cardioverter defibrillator): At present, implantation of an automatic ICD (implantable

cardioverter defibrillator) is the only treatment proven effective in treating ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation and preventing sudden cardiac death in patients with the Brugada syndrome. Risks for asymptomatic patients with typical

electrocardiographic patterns are the same; a third will develop ventricular

tachycardia or fibrillation within two years.

• Patients with Brugada syndrome and a history of cardiac arrest must be treatment with an ICD.

• Studies have suggested that asymptomatic patients with no family history of sudden death can be managed conservatively with close follow up without an ICD.

• However, another study suggested that inducible ventricular fibrillation in asymptomatic patients is an indication for ICD implantation, with the data from a single large study showing a 12% risk of spontaneous VF within 3 years of diagnosis.

• Patients with intermediate characteristics present a most difficult challenge. (Brugada Syndrome Treatment & Management)

• Activity Restriction: Because regular physical activity can increase vagal tone and increase the likelihood of ventricular fibrillation and sudden death, patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome should be advised against competitive sports.

THE LONG QT SYNDROME

(LQTS)

Like the Brugada syndrome, with its characteristic

hereditary ion channel and ECG abnormality, hereditary prolongation

of the QT interval is also associated with SADS (Sudden Arrhythmia

Death Syndrome). LQTS is caused by mutations of the genes for cardiac

potassium and sodium ion channels. The most common type is the autosomal

dominant Romano-Ward syndrome. While it can present with syncope and

seizures, In 30 to 40 percent of patients, sudden death is the only

event. While the cardiac events are usually precipitated by physical

and emotional stress, deaths can also occur in sleep. A history of

unexplained sudden death in a young family member is a clue.

QT prolongation is characteristic and

predisposes to ventricular tachyarrhythmia – polymorphic ventricular

tachycardia, or torsade de pointes, which can lead to ventricular

fibrillation and sudden cardiac deaths. Sometimes, only a borderline

prolonged QT interval is seen. Another clue is the presence of T-wave

alternans, the severity of which correlates with cardiac events.

Some of the highest rates of inherited

long QT syndrome occurs in Southeast Asian and Pacific Rim countries.

The syndrome has more treatment options

than the Brugada syndrome: Beta blockers, potassium, avoidance of

certain drugs, permanent pacemakers, and implantable defibrillators.

THE SHORT QT SYNDROME

A relatively new syndrome, first described

in 1999, belonging to the ion-channel disorders called "channelopathies,"

hereditary short QT syndrome is an autosomal-dominant clinical-electrocardiographic

entity with associated gene mutations. It is characterized by a short

QT, frequently tall-peaked T-waves similar to a "hyperkalemic-T,"

inducible ventricular fibrillation, episodes of syncope, a high tendency

for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or life-threatening arrhythmias,

without any underlying structural heart disease.

Three forms of the syndrome have been identified

affecting different channels. Indicated therapy for those who have

survived a cardiac arrest or those with a history of syncope, is the

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. In its absence or inaccessibility,

drug therapy has the potential for prolonging the QT interval. However,

drug therapy has been shown to be beneficial only for the first form,

and ineffective for the other forms.

Although it has been linked to deaths in infants,

children and young adults with a family background history of sudden

cardiac death, it is possible that many survive into a later adulthood,

into the mean age of deaths linked to SUDS/ SUNDS or bangungut.

|

SOURCES

• Sudden adult

death syndrome .Dr Trisha Macnair

•

The Brugada type 1 electrocardiographic pattern is common among Filipinos

• Batibat. Philippine Mythology. Wikipedia

•

What role for autonomic dysfunction in Brugada Syndrome? Pathophysiological

and prognostic implications. Thomas Wichter

• Why would a middle-aged man faint? T. Dajer. Discovery. November

2006

•

Brugada Syndrome: Recognizing the ECG Patterns: A. Joshi, DO,

MBA, David Kleinman, MD

• The Brugada Syndrome. http://www.brugada.org/about/disease-history.html

• Sudden and unexplained death in adult Filipinos / Ronald Munger

& Elizabeth Booton . International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996

• Heart rate variability in patients with Brugada syndrome in

Thailand / R. Krittayaphonga, G. Veerakulb, K. Nademaneec and C. Kangkagate

* Genetic and biophysical basis of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), a disease allelic to Brugada syndrome / Matteo Vatta, Robert Dumaine, George Varghese, et al /

Hum. Mol. Genet. (2002) 11 (3): 337-345./ doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.3.337

• Nightmare death syndrome / David Hambling / http://www.forteantimes.com/strangedays/medicalbag/335/nightmare_death_syndrome.htm

• Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndrome: Importance of the Long QT

Syndrome . J.MEYER, MD. et al/ AmAcadFamPhysician./ August 2003

• Genetic and biophysical basis of sudden unexplained nocturnal

death syndrome (SUNDS), Human Molecular Genetics, 2002, Vol. 11

• Asian genetic killer found in Polynesian men. Danny Kingsley

– ABC Science Online

• Long QT Syndrome / Ali A Sovari, MD /Medscape Reference

• Brief Review of the Recently Described Short QT Syndrome and

Other Cardiac Channelopathies . Andrés Ricardo Pérez

Riera, M.D.**Cardiology Division, ABC's Faculty of Medicine, ABC Foundation,

Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil,

• Short QT syndrome / Ramon Brugada, Kui Hong, Jonathan M. Cordeiro

and Robert Dumaine / CMAJ November 22, 2005 vol. 173 no. 11 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050596

• Sudden death in sleep of Laotian-Hmong refugees in Thailand:

a case-control study. R G Munger. m J Public Health.1987 Sept; 77(9):

1187–1190

• Sudden

Arrhythmia Death Syndrome: Importance of the Long QT Syndrome. / John

Meyer et al / Am Fam Physician. 2003 Aug 1;68(3):483-488.

• Essential EKG Information for EMTs & Paramadics / Dr. Dale Dubin

• The Brugada type 1 electrocardiographic pattern is common among Filipinos / Giselle Gervacio-Domingo, Jessore Isidro, Jose Tirona, Eden Gabriel, Gladys David, Ma. Lourdes Amarillo, Dante Morales, Antonio Dans/ Journal of Clinical Epidemiology Volume 61, Issue 10 , Pages 1067-1072, October 2008

• Brugada syndrome (EKG patterns) / Napolitano C, Priori SG./ Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006 Sep 14;1:35

• Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association / Antzelevitch C; Brugada P; Borggrefe M; Brugada J; Brugada R; Corrado D; Gussak I; LeMarec H et al / Circulation. 2005; 111(5):659-70 (ISSN: 1524-4539)

• Controversies in Cardiovascular Medicine / Patients With an Asymptomatic Brugada Electrocardiogram Should Undergo Pharmacological and Electrophysiological Testing / Pedro Brugada, MD, PhD, FESC; Ramon Brugada, MD; Josep Brugada, MD, PhD / Circulation., 2005; 112: 279-292 /

doi: 10.1161/?CIRCULATIONAHA.104.485326

• Brugada Syndrome in Children / Don't Ask, Don't Tell? / Editorial / Sami Viskin, MD / Circulation, 2007; 115: 1970-1972 / doi: 10.1161/?CIRCULATIONAHA.106.686758

• Brugada Syndrome Treatment & Management / Jose M Dizon, MD; Chief Editor: Jeffrey N Rottman, MD / Medscape Overview

* Alcohol-induced ventricular fibrillation in a case of Brugada syndrome / Kimie Ohkubo, Toshiko Nakai, and Ichiro Watanabe / doi:10.1093/europace/eut009

|

We sleep to wake. .

. but sometimes, sleep becomes brother to death. . . leads us helpless

to a nightmare's dance. . . and we waken no more.

We sleep to wake. .

. but sometimes, sleep becomes brother to death. . . leads us helpless

to a nightmare's dance. . . and we waken no more.

FOLKLORIC TREATMENTS

FOLKLORIC TREATMENTS

The

human body has a system of quasi independent electrical circuits that

can be recorded through medically dedicated tools: the EMG-NCS (electromyography

for muscle and nerve conduction studies), the EEG (electroencephalography

for the study of brain waves) and the EKG or ECG (electrocardiography

for a print out of the heart's electrical rhythm). Fascinating, all

– electrical systems working in unison, with an endogenous power

source that usually lasts a "lifetime of average use and abuse."

Of these, it is the EKG that can provide information critical to the

immediate assessment and management of life-and-death

situations: heart

attacks and potentially fatal cardiac irregularities. To boot, it

can provide clues of rhythm disturbances and

PQRST-wave configuration abnormalities that can alert the astute clinicians

into raising red-flags, recognizing and preventing potential problems.

The ECG has been the gateway tool in the diagnoses of clinical entities

constituting a group called SADS (sudden

arrhythmia death syndrome) recognizable by its potentially fatal electrocardiographic

presentations (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, idiopathic ventricular

fibrillation,

or arrhythmias caused by electrolyte imbalances). Recent studies and

discoveries have focused on emerging entities — the Brugada

syndrome, the long-QT and the short-QT syndromes — with its

hereditary genetic defects affecting the cardiac ion channels, stripping

some layers from the myths of sudden unexpected nocturnal deaths,

providing science, etiologies and treatment options.

The

human body has a system of quasi independent electrical circuits that

can be recorded through medically dedicated tools: the EMG-NCS (electromyography

for muscle and nerve conduction studies), the EEG (electroencephalography

for the study of brain waves) and the EKG or ECG (electrocardiography

for a print out of the heart's electrical rhythm). Fascinating, all

– electrical systems working in unison, with an endogenous power

source that usually lasts a "lifetime of average use and abuse."

Of these, it is the EKG that can provide information critical to the

immediate assessment and management of life-and-death

situations: heart

attacks and potentially fatal cardiac irregularities. To boot, it

can provide clues of rhythm disturbances and

PQRST-wave configuration abnormalities that can alert the astute clinicians

into raising red-flags, recognizing and preventing potential problems.

The ECG has been the gateway tool in the diagnoses of clinical entities

constituting a group called SADS (sudden

arrhythmia death syndrome) recognizable by its potentially fatal electrocardiographic

presentations (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, idiopathic ventricular

fibrillation,

or arrhythmias caused by electrolyte imbalances). Recent studies and

discoveries have focused on emerging entities — the Brugada

syndrome, the long-QT and the short-QT syndromes — with its

hereditary genetic defects affecting the cardiac ion channels, stripping

some layers from the myths of sudden unexpected nocturnal deaths,

providing science, etiologies and treatment options.